Samuel Waldo (1783-1861) and William Jewett (1795-1873). John Pintard, 1832. Oil on wood panel. The Louis Durr Fund, 1928.1.

Unlike most upper-class New Yorkers who had left the city by the height of the 1832 cholera epidemic, John Pintard (1759-1844) remained and reported that summer’s events in letters to his daughter in New Orleans. Pintard belonged to that first generation of post-Revolutionary municipal leaders who considered civic duty on par with material progress; he was a leader in many charitable and educational organizations, and in 1804 founded the New-York Historical Society. But, also typical for his class, he held the notion that those who contracted cholera had brought the wrath of God upon themselves by leading lives that lacked moral restraint. On July 13th he wrote:

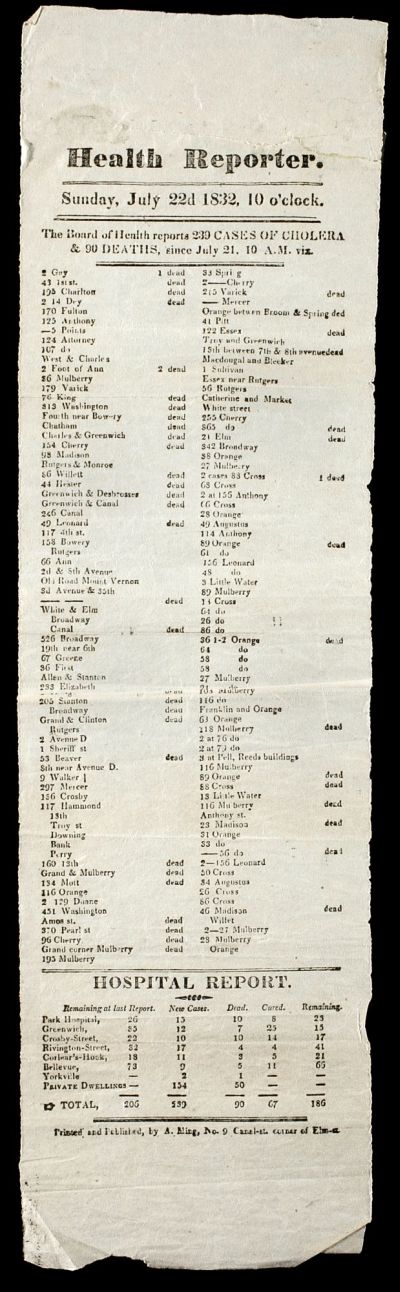

At present it is almost exclusively confined to the lower classes of intemperate[,] dissolute & filthy people huddled together like swine in their polluted habitations. A visitation [of cholera] like the present may work beneficially to promote Temperance, proving a blessing instead of a curse.

And on July 19th:

We have a very heavy report this day, whi[ch,] however[,] does not in my opinion increase the cause for alarm. Those sickened must be cured or die off, & being chiefly of the very scum of the city, the quicker [their] dispatch the sooner the malady will cease.

Pintard wrote his daughter that the book he held in the portrait was the then immensely popular The Holy Bible Containing the Old and New Testaments; with Original Notes, and Pracitcal Observations, by the Rev. Thomas Scott, open to Psalm 90 (Lord, thou hast been our dwelling place in all generations), “my favorite com[mentar]y & psalm, both well adapted to my taste and years.” Scott’s commentary read, in part:

The sentiments indeed of the psalm are never unsuitable to our situation in the world: but they would be particularly adapted to the case of a pious man, in a time of pestilence, when thousands were swept away on every side of him.

Pintard’s complete cholera-related correspondence may be found in volume 4 (covering 1832-1833) of Letters from John Pintard to his Daughter Eliza Noel Pintard Davidson, 1816-1833 (New York: Printed for the New-York Historical Society, 1941). The book is available for perusal in the N-YHS library.